Contents

Phishing Your Own Employees With COVID-19 Lures Is Evil

This essay is a part of the honest.security initiative at Kolide. Our organization does not offer phishing training products or services.

The COVID-19 vaccine roll-out plods forward. A few more drops of information about vaccination schedules, locations, or eligibility drip out of official government channels and trusted news sources every week. And every week, we wait for our turn to roll-up our sleeve, get jabbed in the arm and get on with our lives. The tension is palpable, and email scammers and criminals have taken notice.

Preying on our collective anxiety, cybercriminals have updated the lures they use to phish their vulnerable targets successfully. These lures include enticing promises of special offers to skip the vaccination priority line and secret information about clinics with nearly expired doses eager to vaccinate anyone who wanders in at just the right moment. Desperate for any information, even the most vigilant employees can be easily tricked — hook, line, and sinker — into sharing login information or downloading malicious software onto their laptops.

Employers’ IT and security teams rely on tried and tested phishing training software to tackle this problem. This software simulates these fraudulent emails, but instead of compromising employees’ devices, it flags the recipient for additional training and support when they take the bait. But companies who have successfully relied on this style of training for years are suddenly reeling from the backlash from outraged end-users. These incensed employees call into question the ethics and morality of intentionally spreading misinformation about vaccinations.

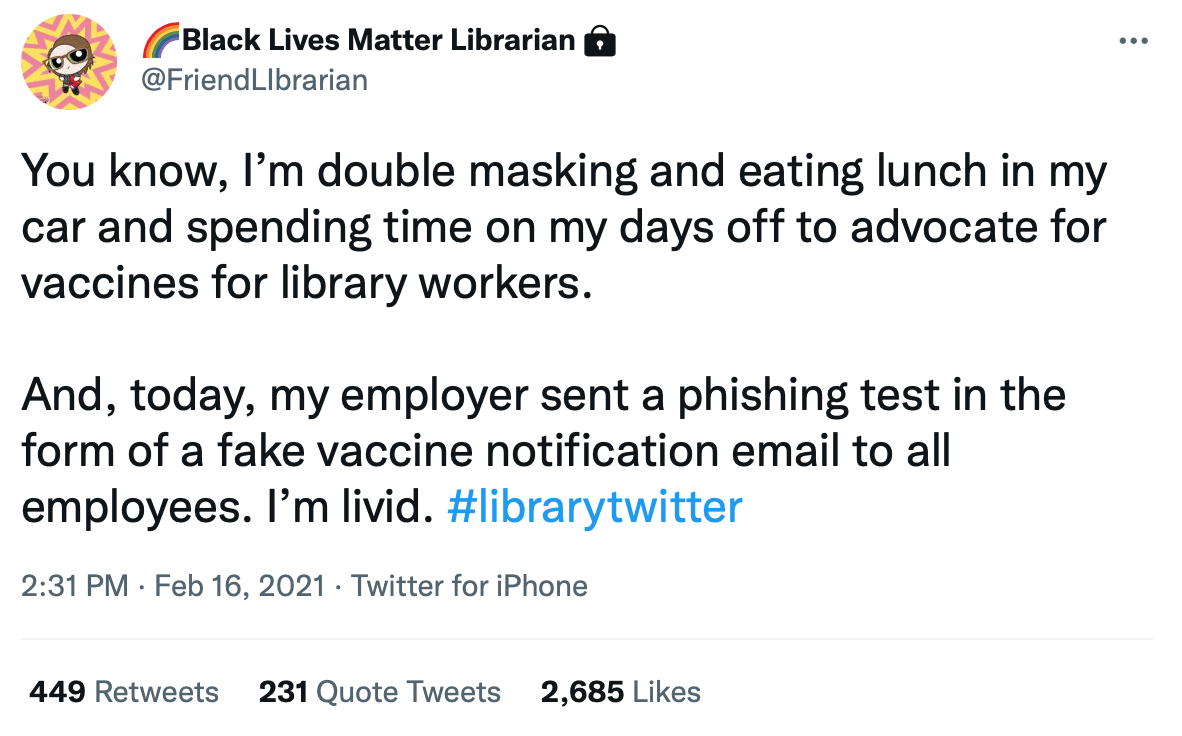

One librarian on the receiving end of one of these training emails took to Twitter to express her disgust:

In September, just as US coronavirus deaths reached 200,000, Tribune Publishing (the publishing arm of the Chicago Tribune, among others) sent a phishing simulation that promised staff a 5,000–10,000 dollar bonus as a thank you. Baltimore Sun crime and courts reporter Justin Fenton who was the recipient of such an email was one of several disgruntled employees that put the company on blast:

After slashing our staff, closing newsrooms, furloughing reporters and cutting pay during a pandemic, @tribpub thought a neat lil way to test our susceptibility to phishing was to send a spoof email announcing large bonuses. Fire everyone involved. pic.twitter.com/tFZsSNrf30

— Justin Fenton (@justin_fenton) September 23, 2020

In December, web hosting company GoDaddy experienced similar public backlash when it was reported they sent their employees a simulated phishing email that included the promises of a 650 dollar bonus. People who clicked the link to receive money to make rent, put food on the table, or place presents under the tree, instead found a humiliating message that their own organization’s security team had tricked them.

There is a school of thought in the information security community that if bad actors are using these techniques, then they should be fair game for these simulations. I strongly disagree. While simulating the bad guys can be a potent training technique, it must be used carefully by teams with a strong track-record in empathizing with their employees. When ham-fisted, these simulations damage the relationship between the security team members and employees. Do this enough, and attackers will enjoy greater maneuverability as they exploit the wedge between these groups. To address this problem, organizations should consider the following techniques to help blunt these attacks without the cultural fall-out.

Announce Before Testing (Or Skip The Test Entirely)

It may seem counter-intuitive, but pre-warning employees about phishing simulations actually improve their effectiveness. Phishing simulations are the final test at the end of what should be a comprehensive education effort.

Even on perfectly trained staff and with innocuous lures, phishing simulations can waste precious time as people needlessly discuss and research a manufactured threat. Because of this, they should be done sparingly (no more than once a financial quarter) as a means of measuring the effectiveness of the security team’s ability to educate. They should not be used as an indictment of specific employees.

If the security team insists on phishing simulations, ensure they do the following before hitting send:

- Briefing all staff on the specific lures with examples in several venues (email, chat, physical postings)

- Verifying the suitability of the content of any simulation with HR and legal

- Pre-announcing when the simulation will occur with the provided full-text of email

- Preparing for a full post-mortem to all employees once the training is complete

Fill The Information Gap

These phishing lures are so effective because they exploit the confusion created by the absence of good information. One way organizations can diminish these lures’ potency is by providing employees with officially sourced information in the venues they use every day: Slack, email, and other internal collaboration software.

While links of resources in a portal are a good starting point, consider creating spaces for discussion between employees in chat software like Slack or Microsoft Teams. These spaces are a great place to deploy homegrown bots and apps that can post updates about vaccine eligibility and regional lock-down announcements. Unlike email, chat software like this comes with the added benefit of being closed to untrusted outsiders. This makes it nearly impossible for bad actors to leverage this platform for phishing.

Finally, it’s always good practice for organizations to regularly specify what they would never do or ask, like asking employees for private healthcare details directly or pre-empting regional governments’ vaccination efforts.

Incentivize Staff To Report Security Issues And Follow-up

Security and IT teams generally under-estimate the visibility gained when staff who feel comfortable reporting issues do so. To obtain the most benefit, security teams should look for ways to increase this communication’s bandwidth and quality through incentives.

A great first step is to define an internal program for users to report serious issues to the security team in exchange for a small financial reward. Most organizations already have externally facing programs to pay external security researchers to disclose problems (known as bug bounties). These organizations can, with a little extra effort, expand their scope to cover internal reports.

Even without the financial incentive, creating spaces for employees to report concerning security issues that result in attention and prompt follow-up will break down many of the natural adversarial barriers that can naturally form between these parties.

Final Thoughts

Criminals will continue to make hay with misinformation campaigns that target vulnerable employees. While simulating these attacks in the form of phishing lessons can help raise awareness within an organization, it must be done with care and oversight outside of the company’s security and IT functions. Failing to do so could inflame internal tensions between IT teams and staff and potentially even spill out into an embarrassing public relations issue.

Instead of reaching for simulation-based training as the first step, organizations should embrace more direct and effective means for combatting these threats and focus on building a relationship of honesty, transparency, and collaboration between end-users and security staff.